The Construction of Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B

A very personal and technical written and photographic history, by James MacLaren.

Page 46: Getting Ready to Roll.

| Pad B Stories - Table of Contents |

The Towers of 39-B.

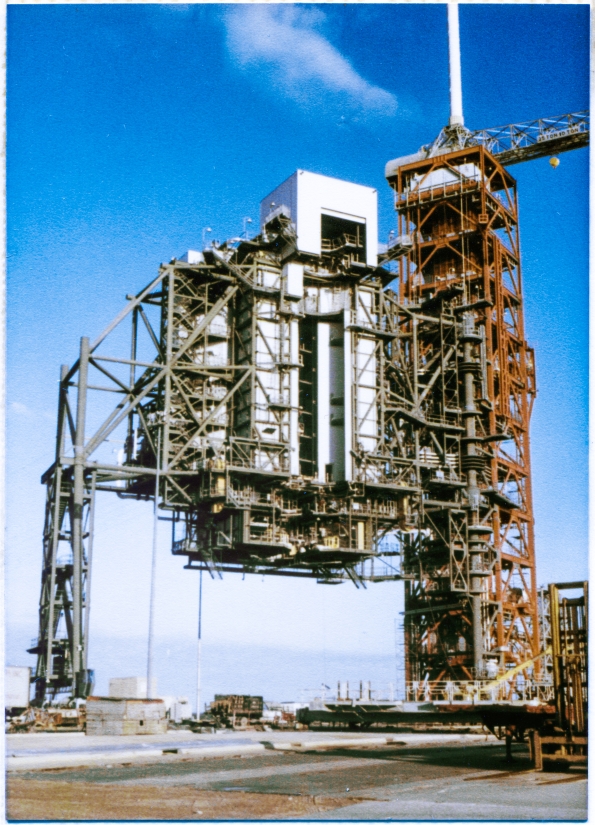

It is another clear Florida Morning, and we are not far away from our first full-up rotational test of the RSS, driving it for the first time, along its curved rail, out and across the Flame Trench to its mate position where it will be doing its work, servicing Space Shuttles.

You are by now presumed to have a sensible working familiarity with most of what you're seeing.

So let's take a quick break from all of that technical stuff, and instead, how about we insert an image of the thing this whole facility was originally designed and built to service in the first place, ok?

How about we insert the Space Shuttle into this image?

That might be kind of fun, right?

Let's see what it looks like that way, and maybe get a bit of perspective on both the Towers, and the Shuttle, in so doing.

And so I went fishing on the internet, looking for a suitable image of the Orbiter, and although it's far from perfect, what I found, which is STS-3 flying overhead prior to landing at White Sands in New Mexico (because of bad weather at both the primary landing facility at Edwards, and the backup landing facility at KSC, forcing the use of the backup backup landing facility at White Sands and it was the one and only time that ever happened), seems to be close enough.

Or at least for our present purposes, it is, anyway.

So ok.

So here you go, Pad 39-B, RSS in the demate position, with Columbia sitting there right where it would go if the RSS was mated to it, sitting on its MLP, which of course it's not.

We've come far enough along with our journey of understanding The Pad that there are beginning to be less and less things in each new image that we have not already visited in one way or another, and this is testimony to the vast amount of information we have gained about Launch Complex 39-B up to this point.

The image at the top of this page is quite instructive in this regards, and contains little that we have not already covered, but there remain a few things yet, and although it's not displayed very well at all, this might be as good a place as any to point out and discuss the Engine Service Platform, sitting low above the concrete of the Pad Deck, spanning the width of the Flame Trench.

I'm addressing the Engine Service Platform now, despite having to use a particularly-poor image of it, because we're getting close to the end of these photo-essays, and if I do not do it now, I will not be able to do it at all, so please accept my apologies for failing to get a better picture of it when I was out there, but it was not to be, and we'll just deal with what we have, and be glad we have anything at all to work with, ok?

We've seen it before, way back on Page 9 on our very first visit to high steel, but it's not displayed very well at all there, either, and it wasn't part of the RSS which we were focusing on at the time, and so I let it go.

But now we've run out of time, and so we must. With what we've got.

The ESP rolled on rails that ran just inboard of the two crawlerway trackways, and it could be rolled a pretty good ways down the pad slope to a park position when not in use, or it could be brought all the way up to a position on the pad deck where it sat directly beneath the MLP, and where you're seeing it in the image above is somewhat intermediate to those positions, which it where it stayed for most of the time I was out there.

It was a big item, solid steel, spanning the 58 foot width of the flame trench, was built sturdy to carry some substantial loads, and had a footprint perhaps of similar size to the front lawn, and maybe part of the house, in a typical American suburban subdivision.

It was low and wide and strong, and it was used to place additional platforms on top of it that could be extended vertically for use when it was under the MLP, to provide access to the Space Shuttle's engines (hence its name Engine Service Platform), should it become necessary for personnel to get to them once the bird was on the pad.

And the story was told, whether true or not I do not know at this time, but the people who told it to me (more than one person, more than one occasion, and all of them were Good, Stand-up, People, that I never found the first reason to ever doubt), said that during Apollo 10, which was the only moon mission that flew on a Saturn V from Pad B, the people in charge of the launch, for unknown reasons, did not roll the ESP quite all the way down the pad slope, but instead simply pulled it back most of the way and left it there.

The story goes on to say that when the Saturn V lit up and took off, the volcano of exhaust coming up and out of the south end of the flame trench managed to catch the north edge of the ESP, and flipped it into the air and kicked it all the way down to the bottom of the pad slope, a distance of roughly an eighth of a mile.

Giant steel contraption, bigger and heavier than your house, flipped like an empty pizza box, an eighth of a mile!

I strongly suspicion that this story is true.

That goddamned Saturn V was just something else. Something beyond proper human understanding.

And now that we're getting down toward the close of things with my time working for Sheffield Steel, perhaps it might be good time to see just how far we've come.

Before and after. Not from the very beginning, not to the very end, but close. Close in both directions. Close as I'll ever be able to show you with the photographs I've taken. I've said it before. The heavy iron goes fast. It's all the light stuff which comes later that takes up so much time. These two images are a fairly good illustration of that.

Return to 16streets.comACRONYMS LOOK-UP PAGEContact Email Link |